- Home

- News

- Cities & District Energy News

- Four lessons from Europe’s climate leaders

Four lessons from Europe’s climate leaders

- Cities & District Energy News

- 09 May 2017

- by Citiscope

Article published on Citiscope

What do Europe’s leading cities have in common when it comes to cutting greenhouse-gas emissions?

That’s a question I’ve been looking into while researching a book on how to address the problems of climate change. As an energy and natural resource specialist with a deep interest in climate, I’ve been struck by the progress that cities from the Netherlands to Scandinavia have been making in slashing emissions.

During recent visits to Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Rotterdam and Stockholm, I spoke with city and business leaders to learn their most effective tactics and strategies. In all cases, these cities began with bold carbon-reduction targets and then followed up with thoughtful, methodical long-term plans to get the job done. But that was only the beginning.

Here are some of the valuable lessons I learned from these in-depth conversations that city leaders around the world might find useful.

1. Look for partnerships

Local authorities can’t do it alone. That’s evident in the way Amsterdam is working to achieve its sustainability plans. The city is systematically seeking agreements to reduce carbon emissions with industries, supply-chain managers and real estate developers, as well as bus and taxi companies.

It hasn’t always been easy. For example, Amsterdam’s bus and taxi companies originally opposed the city’s climate and energy programme out of concern it would increase their costs. But city officials successfully enlisted the cooperation of both groups, reaching agreements with both the municipal bus company and taxi fleet to switch to all-electric vehicles by 2025.

To encourage the taxi companies to join the program, the city installed some fast charging stations for taxis and gave electric taxis preferential treatment at certain city taxi stands during the transition. Taxi drivers now have shorter waits for their fares, making the switch to EVs more profitable. Now, the city is studying how to make municipal ferries cleaner.

As part of a deal with delivery companies, Amsterdam is increasing the number of freight transfer hubs on the outskirts of the city. There, gasoline and diesel-powered commercial vehicles are encouraged to transfer cargo to low-emission or zero-emission vehicles and to combine loads to reduce the number of delivery trucks in the city.

Partnerships are also important in Copenhagen. That city has teamed up with utilities, for-profit companies, nonprofits and research institutions, so that a broad cross-section of society has a stake in the city’s clean-energy transition and a role to play in it.

For example, Energy Leap is a public-private partnership designed to overcome an obstacle to reducing energy use in rental apartment buildings. In such buildings, renters often don’t stay in an apartment long enough to make energy-efficiency investments pay off. Even if they wanted to invest in new insulation, windows, or roofing, they would be spending their own money to improve someone else’s property. Likewise, landlords don’t have an incentive to invest either, as tenants are typically responsible for paying the energy bills.

Energy Leap helps the major stakeholders find ways to surmount these and other obstacles by sharing the resulting benefits. The city has recruited 22 major building owners, administrators, and housing associations as partners to cut heating and power needs in buildings. Energy Leap’s goal is to enroll partners managing at least 17 percent of the city’s building stock, and to thereby reduce 6,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions a year by 2025.

2. Make it convenient to go green

Making climate-friendly choices shouldn’t have to be an alternative lifestyle. Smart cities are making it easy for residents to do the right thing.

That’s the philosophy in Rotterdam, where a programme called Power Surge strongly encourages residents to switch to electric cars. Rotterdam already provides 2,000 charging stations for electric vehicles, and is adding 2,000 more. As one added inducement, the city offered free parking permits for the first 1,000 vehicles to register for the programme. As another, electric car owners get a free charging point from the city.

Even as the city makes it easier to use electric vehicles, it’s making it harder to use polluting ones. Starting in January, Rotterdam prohibited older, high-emission cars in a large zone of the city centre.

“When you talk to the public about CO2 emissions, it doesn’t appeal to them very much,” says Paula Verhoeven, manager of the Rotterdam Climate Initiative, which the municipality created. “But by focusing on air quality, it makes [public] acceptance higher.”

Rotterdam also is promoting the use of electric bicycles and scooters, and pays owners of conventional scooters a fee for scrapping them. The city has a dozen public bicycle sheds with recharging stations for electric bicycles and scooters.

“We also have a subsidy in place to [encourage people to] replace their old car or buy a new one if they like,” Verhoeven says. “Or they can get rid of their car altogether and just use public transport, which is excellent in the city.”

3. Reuse energy and natural resources

Waste nothing. That’s an attitude some European cities have adopted to reduce the energy used in heating buildings — especially in cities fortunate enough to have district heating systems that deliver heat to buildings through networks of pipes. (Some cities also offer district cooling.)

Stockholm has a vast district heating system with nearly 3,000 kilometres of underground heat pipes that supply four-fifths of the city’s heating needs. The system captures waste heat from power plants and industries and shares it with homes and more than 10,000 large buildings.

Sustainability Manager Ulf Wikström manages the system for the local utility, which is co-owned by the city of Stockholm and the power company Fortum. “What people don’t know is that quite a big part of the district heating is produced from energy recovered from wastewater coming from households and industries in Stockholm,” Wikström says. “It’s a very good energy source.”

While generally cooler than room temperature, wastewater remains warm enough that Stockholm’s ultra-efficient heat pumps can extract energy from it. Overall, some 80 percent of the heat provided by the district heating system comes from renewable energy sources, including some from biogas recovered by composting the city’s household food wastes. Some of the biogas is used to fuel the cities buses.

The city encourages businesses with significant cooling needs, such as large data centres, to sell the heat generated by computers and electrical equipment to the utility. One megawatt of heat continually exported from a data centre will generate a revenue stream of USD 200,000 a year, according to Jonas Collet, head of media relations for the utility, Fortum Värme.

Rotterdam’s district heating system is not as extensive as Stockholm’s. Less than 20 percent of Rotterdam’s homes are now on district heat. Still, the city is aiming to reuse as many natural resources as it can.

In the city’s strategic sustainability and climate plan, Investing in sustainable growth, Rotterdam Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb and Vice Mayor for Sustainability Alexandra van Huffelen declare that by 2042, “Rotterdam … will have been transformed into a system of recycling streams of water, energy, raw materials, goods and waste products: a network of information and knowledge, of synergy and vigor.”

Rotterdam’s industries and incinerator generate enough waste heat for a million households. This city of 630,000 thus has substantial potential to share that heat with homes and businesses. An entity known as the Heating Company of Rotterdam already collects waste heat from industries in the port and shares it with homes and businesses.

Use of waste heat eliminates the need to burn fossil fuels for heat and results in a significant reduction in greenhouse gases while reducing air pollution. The energy from combusting a single bag of garbage is enough to provide heat for seven showers, officials say.

District heating is integral to Rotterdam’s plan to eventually phase out natural gas and reduce carbon emissions. The city is committed to getting 40 percent of its residents on district heat by 2020 and aspires to have 50 percent connected to district heating by 2035.

Amsterdam is already reusing municipal waste to co-generate heat and power for some residents. The waste is collected and delivered to a central incinerator with advanced pollution controls. Heat from the plant is distributed to households in large insulated pipes, replacing individual gas furnaces.

Excess heat from a gas-fired power plant on the east side of Amsterdam serves residents in the city’s southern and eastern quadrants. Meanwhile, the city plans to create a regionwide heat network.

Amsterdam is also stepping up recycling of concrete. All concrete for future municipal road building projects in Amsterdam will use recycled concrete. That will be “a huge CO2 reduction,” according to Peter Paul Ekker, a mayoral assistant. Globally, the production of cement (the main ingredient in concrete) generates about five percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions.

4. Stress economic payoffs and quality-of-life benefits

While it’s easy to dwell on the calamitous impacts of climate change in terms of rising seas and severe weather, smart city leaders stress the positives. There are economic and other opportunities in pursuing these kinds of local climate solutions.

Since 2009, Copenhagen has not just been narrowly focused on cutting carbon dioxide emissions. It has instead been determined to show the world that it is possible to combine growth, development, and quality-of-life improvements with radical reductions in emissions.

Thus the city’s plan is to become greener, more efficient, more liveable, more competitive, and more prosperous. A drive to make the city carbon neutral by 2025 is framed as an effort to create new jobs, innovation, investment in green technologies.

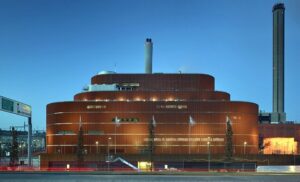

Every time Copenhagen spends one dollar on its climate plan, it generates USD 85 in private investment elsewhere in the city, according to the city’s climate director Jørgen Abildgaard. It takes the form of investment in new buildings, in building retrofits, in different kinds of mobility services, and in new infrastructure, such as the city’s new incineration plant and district heating system.

Why is there such broad support for the Copenhagen’s climate goals?

According to Morten Kabell, the mayor for technical and environmental affairs, “Going green is good for the economy. It’s good for creating more jobs. It’s good for actually having a vibrant city, and it’s part of making cities more liveable, which is a key component today in a [competitive] economy.”

The transformation from what Kabell calls the old, fossil-fired “black sectors” of the economy to the modern green ones is creating both white-collar and blue-collar jobs. “You also see it in the cleantech sector of Copenhagen,” Kabell says, “where exports have been growing by 12 percent a year.”

As the Danish government subsidized renewable energy, it created a whole new energy technology sector for Denmark. Within 15 years, the technology sector has come to rival the country’s agricultural sector, which had been its dominant industry for centuries. The wind energy business in particular has been good for Denmark, especially offshore wind development.

It’s a similar story in Amsterdam, explains Ekker. The municipality rallies support for reducing carbon emissions not by debating the impacts of climate change or scaring the public, but by calling its climate policies “sustainability measures” and underscoring their economic and public health benefits.

“Our analysis is that the public in general doesn’t need convincing on the need for mitigation measures,” Ekker says. “But it does need examples and solutions on how to become a sustainable economy.”

City officials therefore talk about what is technologically possible and cost-effective, along with the co-benefits of sound climate policies, such as cleaner air and fewer respiratory problems for people. The city’s progressive policies on electric vehicles have paid tangible economic benefits, such as luring Tesla’s European headquarters to locate in Amsterdam.

Moving away from fossil fuels has real economic benefits, Ekker says, and “we are not afraid to celebrate that.”

Latest News

-

-

26.10.2021 Celsius Summit 2021 – Energy Democracy

26.10.2021 Celsius Summit 2021 – Energy Democracy